Selling Style I: The History of Fashion Marketing Through the 19th Century

By Cameron Walker

Before magazines, before fashion shows, before Instagram, the arbiters of style used very different media to dazzle the public and create demand for their designs. From traveling dolls and the first fashion magazines to smartphone apps and personalized online ads, the marketing of fashion is undergoing an ever-accelerating evolution — with no signs of slowing down.

Join the NC State Wilson College of Textiles on a three-part journey as we discover the history of fashion marketing and predict its future.

Through the 18th Century

Pandoras

For 400 years, the fashionable few relied on Pandoras, or fashion dolls, to discover the clothing styles of the moment. Mini mannequins wore detailed, meticulously constructed costumes for tailors to copy, from the patterned silks and elaborate headdresses of the 15th century to the empire silhouettes of the late 18th. These dolls were well traveled, crossing oceans and enemy lines to ensure their patrons were dressed à la mode — some even carrying their own diplomatic passports.

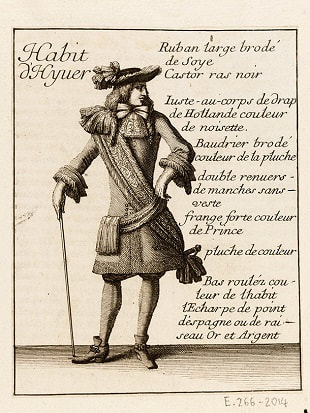

Fashion plates hit the scene in the latter part of the 17th century, during the reign of the Sun King, Louis XIV of France, whose court was the cradle of the modern fashion industry. The country’s nobles were concentrated at Versailles, kept away from their chateaux and grand estates by a king who wanted his rivals close — so they had only their clothing by which to display their wealth and status.

The advent of the boutique and fashion journals like “Le Mercure Galant” (launched in 1678) disseminated their style to the middle class; however, once that style was translated to fashion plate and copied by the bourgeoisie, the courtiers quickly moved on. This was the dawn of fashion as we know it — of the “season” and the perennial pursuit of sartorial novelty.

For the next couple hundred years, fashion plates depicting the latest styles were the premier method of fashion marketing, especially during the reign of Marie Antoinette in 18th century France. Like a historical street-style blog, court fashion was copied down for posterity — captured in a drawing, then engraved in wood, printed onto paper and hand-colored.

These illustrations were sold to the wealthy by subscription in series of sets called “cahiers,” and served as inspiration for dressmakers and “marchandes de modes” — stylists who sold ribbons, trimmings and other adornments used to make old garments new again.

The most famous of these stylists was Rose Bertin, whose Paris boutique Le Grand Mogul was fronted by large windows displaying artfully arranged merchandise to entice shoppers inside. Bertin introduced the ill-fated queen to the pouf — the infamous, towering powdered and beribboned hairdo much mocked in contemporary pamphlets.

To further her own celebrity, Marie Antoinette encouraged Bertin and pouf co-creator Leonard Autié to spill the details of dressing the queen to the women’s newspaper “Le Journal des dames.” Like a modern influencer, the royal wanted to cement her name and image as synonymous with fashion — this worked a little too well, since her image as conspicuous consumer later led to a date with the guillotine during the French Revolution.

19th Century

Fashion Magazines

As the middle class expanded in the 19th century, the ladies’ magazine became increasingly popular. Tailored to different audiences, these magazines were full of royal gossip, embroidery patterns, serialized fiction and more. “Godey’s Lady’s Book” launched out of Philadelphia in 1830 and grew to a circulation of 150,000 a month. Each issue featured literary works, full color fashion plates and a section called the Work Department, with patterns for sewing, knitting and crochet.

1852 saw the launch of the “Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine,” a periodical targeted specifically to the middle-class housewife. Its pages centered on crafts, cookery and clothes, and later included a paper pattern in each issue so women could make their own version of the latest styles. Advertisements started to tiptoe onto the pages of these magazines, selling gloves, slippers, corsets and sewing machines alongside toothpaste and shoe blacking.

Successful milliner and marketing maven (also abolitionist and women’s rights advocate) Madame Demorest, born Ellen Louise Curtis, had a tremendous impact on American fashion and the way it was consumed. She and her husband, William, built a fashion empire advertising a wide range of products in ladies’ magazines (including their own monthly periodical), selling a line of affordable hoopskirts; her invention, the “Imperial Dress Elevator,” which allowed the wearer to discreetly pull up the hem of their voluminous skirt; a sewing machine that could sew backwards; a cosmetics line and more. In the mid-1850’s, Demorest designed the first mass-produced paper patterns, which made high fashion accessible to the middle class. A decade later, Ebenezer Butterick invented the first sized patterns using tissue paper, followed by the McCall Pattern Company in 1870 and the Vogue Pattern Service in 1899. Paper patterns and the rise of the home sewing machine made this the golden age of home dressmaking.

“Ladies are reminded that any pattern will be sent to them by mail, free, from a baby’s sack up to a gentleman’s dressing-gown, or model for a ball dress, on receipt of price,” read an advertisement in the April 1865 issue of Demorest’s Illustrated Monthly and Mme. Demorest’s Mirror of Fashion. “This is a cheap and expeditious way by which ladies at the antipodes [opposite ends of the earth] can procure the latest styles as soon as they are issued, and thus in a week, reproduce Broadway in the wilds of Texas or Oregon.”

Catalogs

The Homestead Act of 1862 pushed settlers westward across the United States, fueling the growth of the nationwide railroad system and with it, mail order selling. The Montgomery Ward catalog — a single sheet of paper listing 163 items for sale — debuted in 1872; 20 years later, the catalog sold over 20,000 items across its 540 pages. The Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalog launched in 1888 and quickly grew to 322 pages. These catalogs sold an assortment of products, from wigs to baby carriages to actual full-size, pre-fabricated kit homes — but they also did swift business selling ready-made clothing. Across the country, people were sending in their orders for men’s suits and hats; ladies’ skirts and “waists,” or blouses; “bust forms,” which worked like push-up bras; muslin underwear, gloves and stylish oxford shoes.

Ready-made clothing became big business as the European concept of the department store crossed the pond. Retailers made a number of marketing innovations — the switch from haggling to set prices, a focus on customer service and experience, and the establishment of strong brand images.

Department Stores

Alexander Turney Stewart opened his Italianate behemoth, the Marble Palace, on Broadway in New York City in 1848; he was among the first to set fixed prices for his wares and lure customers with special sales and fashion shows; he also made an early fortune through mail-order business.

In 1862, Stewart built a new store — this time, an iron palace — several blocks away, in a shopping district that became known as the Ladies’ Mile. This stretch of Broadway was home to upscale department stores like Macy’s and Lord & Taylor, whose large plate glass windows displayed luxurious, fashionable goods in extravagant competing tableaux.

These giant department stores sold almost everything, but were created with women in mind. For the first time in American society, middle and upper class women had a “respectable” place to gather and shop outside the home.

Until places like Selfridge’s and Wanamaker’s and Marshall Fields opened, ladies were expected to remain and entertain in the home. These large, clean, female-staffed emporiums changed society; as shopping became an acceptable hobby, establishments like theaters and restaurants began catering to women, too. The taboos against working outside the home began to crumble, and as women inched toward economic freedom, advertisements increasingly targeted them.

Print Advertisements

One can imagine life seemed to speed up as citizens of the time were increasingly bombarded by advertisements in flyers, posters, billboards, papers and magazines — all trying to convince consumers they had a problem only the advertiser could fix, from weak back (better buy a Harness Magnetic Corset) to tender feet (you need Whitcomb’s “Flexsole” shoes).

Big department stores and retailers advertised their merchandise and sales in the city’s newspapers; these ads were black and white and mostly text-based, offering a lot of information but not much visual stimulation. Colorful trade cards and posters burst onto the scene in the 1860s as new printing techniques made high-color advertisements popular.

Victorian trade cards were portable pastel illustrations featuring cherubic children, fanciful animals and rosy-cheeked women advertising all manner of products, including fine boots and shoes; celluloid collars and cuffs; many varieties of sewing machines and threads; and fancy hats and bonnets alongside patented medicines, pianos and mincemeat. They were the precursors to both business cards and baseball trading cards, and collecting them was a popular hobby until the turn of the last century.

Posters were a revelation in advertising, featuring joyful explosions of color frequently accompanied by memorable slogans. Jules Chéret was the pioneer of advertising posters; he popularized stone lithography — making printing simple and cost-effective — and elevated ads to an art form with dynamic compositions and layers of bright pigment. He opened his own firm in Paris in 1866, and his work was succeeded by that of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Alphonse Mucha and others advertising soaps and shows, cycles and champagne and cocoa.

Posters caught on in America in the late 1800s; the effervescent (usually female) subjects of these posters served as fashion inspiration, advertising a carefree consumer lifestyle alongside department stores and clothing brands.

Birth of the Brand

The most prestigious brand of this time was that of Charles Frederick Worth, called both “the father of haute couture” and the “first couturier,” according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Englishman established the House of Worth in Paris in 1858 during the Second Empire — the reign of Napoleon III and a time of great change and modernization for the capital city. Paris was the crown jewel of Europe, and Worth dressed its most well-heeled citizens (including the trendsetting Empress Eugénie) in sumptuous, exquisitely-detailed designs influenced by Eastern cultures and history.

Painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Hofburg Collection.

Worth was a bold self-promoter who turned the existing dressmaker-client relationship upside down. Clients used to instruct their clothiers what to make, but Worth’s clients came to him to be told what was fashionable.

His innovations include the bustle, which moved the volume of the circular hoop skirts to the back of the dress (freeing women to more easily care for children, work and walk through doors) and a shorter walking skirt, which was an initially risque but ultimately practical ankle-liberating length.

Worth’s contributions to fashion marketing made even more of an impact. He was likely the first to sew branded labels into clothing, increasing recognition of and fidelity to his brand — a practice nearly ubiquitous today. He was the first to use live models to display his couture collections, and he designed both personal wardrobes and stage costumes for celebrities like actress Sarah Bernhardt and singer Jenny Lind. His name regularly appeared in fashion magazines, making him a celebrity in his own right. His creations were so in-demand that women would journey to France to be fitted for complete House of Worth wardrobes, making him the “It” designer of the day.

Check back next month for more fashion marketing history, including “It Girls,” runway shows, the sartorial impact of World War II, magazines, famous designers and more!

Follow the Wilson College of Textiles:

Twitter: @NCStateWilson

Instagram: @NCStateWilson

Linkedin.com/company/nc-state-wilson-college-of-textiles/

Facebook.com/NCStateWilsonTextiles/

Written by Cameron Walker

- Categories: