The Hard Times and Good Life of Mohamed Mansour

Mohamed Mansour and his older brother Youssef were living the American dream. Together, the brothers from Alexandria, Egypt, heirs to a successful cotton business, were members of NC State’s FarmHouse fraternity, reflecting a mutual agricultural heritage.

Mohamed cruised up and down Raleigh’s Hillsboro Street in the 1964 silver Corvette he co-owned with Youssef and their cousin Ahmed El Maghraby, who was also studying chemical engineering at NC State. Mohamed lived comfortably on the $200 a month his parents sent him. Youssef was a member of the NC State varsity soccer team.

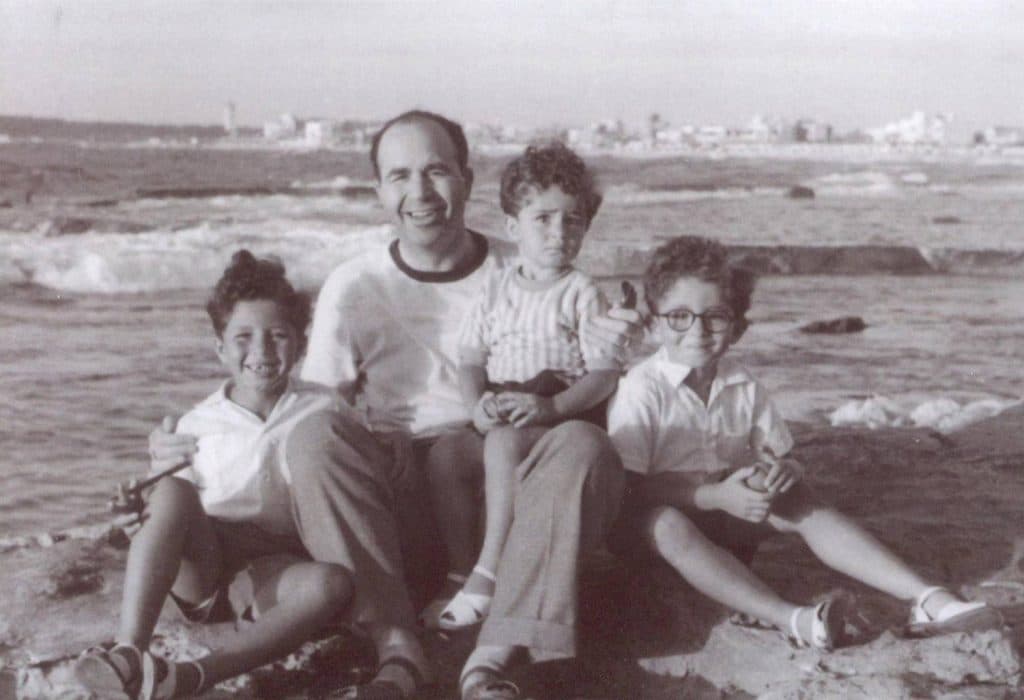

It was an exciting life for young Mohamed, who had enrolled at State College in January 1964 as a 16-year-old aerospace engineering student, following an unlikely recovery from an accident he suffered at the age of 10, when he was hit by a car outside his home in Alexandria.

The near-fatal accident almost cost him his legs, but the stubborn boy convinced his doctors to let him heal without amputation. It took more than three years of being bedbound, watching from the balcony of the family home as his brothers played soccer outside.

He vowed to learn the family business and repay the time his father spent with him during his recovery.

“Son, learn how to communicate and learn how to understand the Western mentality,” Loutfy Mansour told Mohamed the night before the boy left for America, arriving just after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963.

Maybe he learned a little too much of American culture. Self-admittedly, he went to too many fraternity parties. His grades suffered and he was close to flunking out of school. He would have if a caring physics professor hadn’t given him a second chance.

“One of my professors, a lovely man originally from Poland, took pity on me when I pleaded for a second chance,” Mansour says. “He told me plainly — but with a smile and a spirit of generosity — that I could avoid a failing grade but only if I worked harder. He said I had potential, but I needed to raise my game. Fewer parties and late nights. More studying and early mornings. Of course he was right. And I did what he asked.”

Mohamed changed his major from aerospace engineering to textile technology, the perfect place for an heir to one of the world’s largest cotton trading families. He began to excel again in the classroom.

Then one day, the mail arrived and Mohamed, Youssef and their brother Ismail at UNC–Chapel Hill received this devastating news from their parents: “We can’t send you anything anymore. You guys have to take care of yourselves from now on.”

How he and his brothers managed to do that — and return the family’s Mansour Group to one of the largest companies in the Arab world — will highlight Mohamed Mansour’s NC State commencement address on Saturday at PNC Arena, when he returns to Raleigh for a few days of celebration.

Losing the Family Fortune

Back in Egypt in 1952, military ruler Gamal Abdel Nasser had overthrown the country’s monarchy. He became a popular leader in Africa and the Middle East in the mid-1960s, but he also began to nationalize most of the country’s biggest privately owned businesses, including Loutfy Mansour’s cotton trading company. The Mansours lost all their wealth. Loutfy was left with a $75 a month stipend from the socialist government.

Mohamed Mansour sold the Corvette and bought a beat-up Volkswagen Beetle. He moved from the fraternity house to a damp and overcrowded property on Chamberlain Avenue.

The teenager needed a job. He found one at a newly opened Italian cafe on Western Boulevard, earning $1.25 per hour busing tables at Amedeo’s Italian Restaurant. It paid his way through college.

“Slowly I paid off my debts and got into the black,” Mansour says. “I learned to manage my own finances and also to know that spending money is a very different concept as to how you spend your life. They were tough times, but good times. I had no money, and the place where I stayed was a fleapit. But I was happy.

“I was surrounded by friends, supported by my tutors, and embraced by hospitable North Carolina.”

Both Mansour brothers graduated from NC State in 1968, Youssef with a degree in chemical engineering in January and Mohamed with a degree in textiles in May. They both went to graduate school at Auburn, earning Master of Business Administration degrees that eventually helped them re-establish their father’s company. Mohamed stuck around for another two years as a teaching member of the faculty at the Alabama land-grant institution.

Meanwhile, their father joined another cotton trading company in Sudan and again found international success — until the Sudanese government nationalized that company and left the family without income or equity again.

Eventually, Loutfy judged that the commodity markets were too volatile and diversified the family’s new company, starting with a partnership with General Motors. The family went on to partner with Caterpillar and McDonald’s, among other brands, and thrived, even after the father’s untimely death of a heart attack in 1976.

A Rebuilt and Diversified Empire

For nearly 50 years, the Mansour Group has gathered and grown. Mansour Automotive became the largest GM dealership in the world. Mantrac became one of the world’s largest distributors of Caterpillar equipment. The company owns all 90 McDonald’s franchises in Egypt, not to mention the country’s largest chain of grocery stores. ManCapital LLP, the Mansours’ family office based in London, is supporting organizations in diverse sectors from education to clean energy and recently bought an international soccer training academy. A tech enthusiast, Mansour was an early investor in Facebook, Uber and Spotify.

The group as a whole now has more than 60,000 employees in some 120 countries around the world. By revenue, it is the second largest enterprise in Egypt. Mansour and each of his siblings are among their native country’s wealthiest citizens.

Mansour’s charitable enterprise, the Lead Foundation, reveals a bit about his heart. It has provided 4.5 million small and micro loans to impoverished women in Egypt.

His accomplishments have been honored throughout the business world. Last fall, he was presented with the Distinguished Alumni Award by the NC State Alumni Association.

“I turned round what threatened to be my failure at Raleigh,” he says. “I learned that the only way to succeed is hard work. NC State gave me one of the most important things in life: a second chance.

“And I will forever be grateful.”

This post was originally published in NC State News.

- Categories: