The Carpet Conundrum

Written by Cameron Walker

A turquoise carpet became Alex Djuric’s white whale. Eight years ago, he and his wife, Cristine, inherited his father-in-law’s 1967 Mercedes-Benz 250SL convertible. He worked to restore it to mint condition and was able to repair or replace every part of the classic car except one; although he chased down every lead, he could not find a match for the vehicle’s unusual blue carpeting.

“I talked to people in Germany, in China, in India and in Australia — you name it,” he said. “All over the world, I could not find the carpet.”

According to Djuric, out of the nearly 50,000 Mercedes made between 1963 and 1971, only 36 of them had his vehicle’s color combination — a light beige exterior and blue-green interior — so it was important to him that he get that detail correct. From the vehicle’s data card, he determined the carpet was a wool German square weave in color code 6218, or turquoise. He contacted more than 30 vendors in search of the carpet but had no luck. Eventually, a supplier told him that all of the remaining carpet had been stored on the floor of a German warehouse near a riverbank; unfortunately, after a period of heavy rains, floodwaters breached the warehouse and the carpet was destroyed.

Djuric was disappointed, but determined to find his match — so he switched tactics. He retrieved a small patch of nearly mint condition carpet from underneath the seat frame and set about trying to find a supplier who could dye a roll of white woolen carpet to the shade he needed. But again, his search was fruitless.

“I spent thousands of dollars getting samples from (various suppliers) and they couldn’t do it,” he said. “I had one car restorer tell me it would be $10,000 to make the carpet and there were no guarantees it would be an exact match. So I thought, ‘I have to get smart.’”

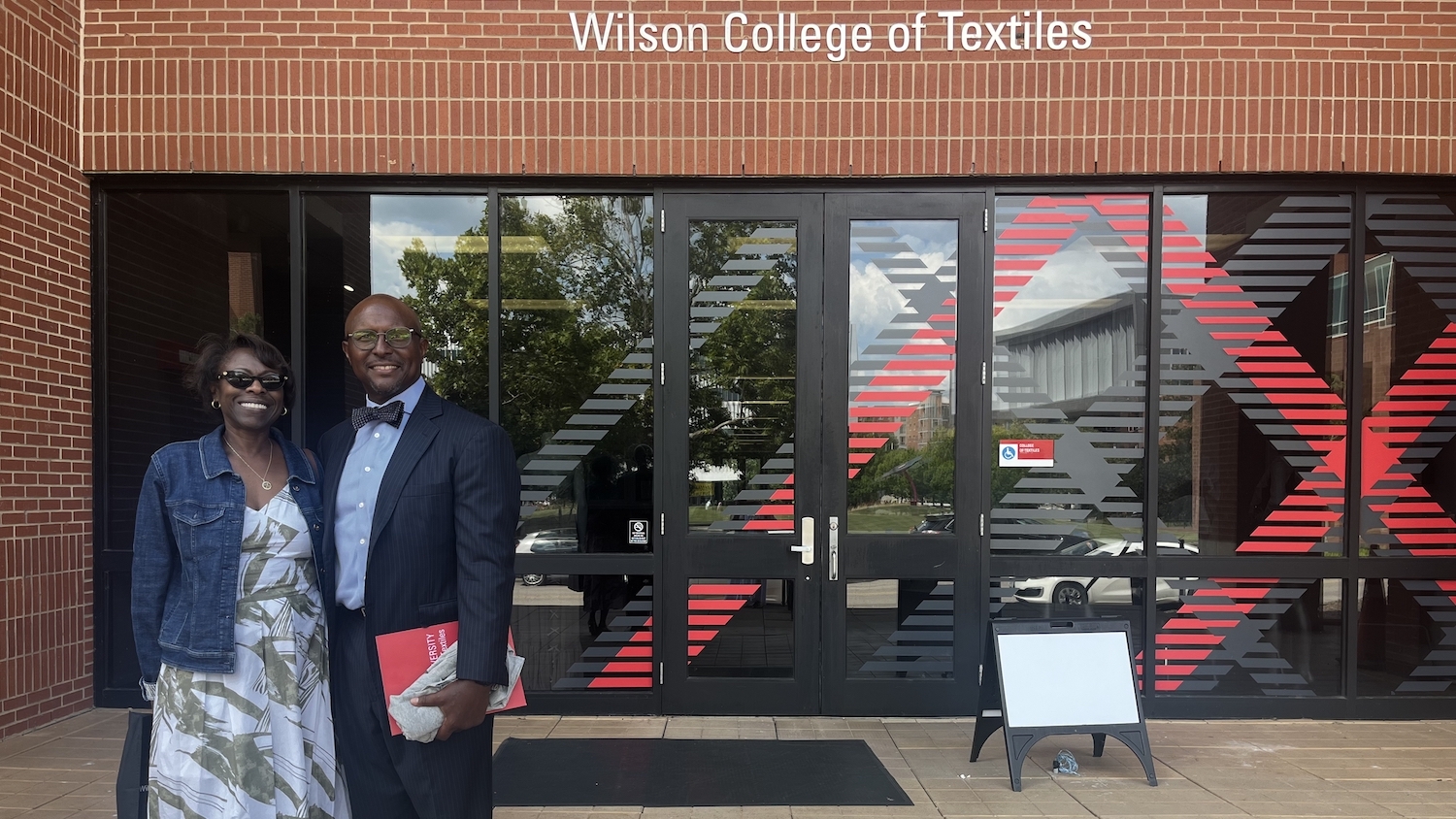

He sought the advice of a carpet dye manufacturer, who suggested he contact Dr. Renzo Shamey at the Wilson College of Textiles. Shamey recommended Djuric reach out to Jeffrey Krauss, Pilot Laboratory manager for the Zeis Textiles Extension (ZTE), which offers prototyping and pilot production through its five laboratories at the College. Djuric was running out of comparison carpet, but he sent in a small sample — about the size of a postage stamp — and Krauss set to work.

“People have ideas that they want to bring to fruition, so we start with small samples and we try to figure out ways to take an idea — whether it be with materials or chemicals — and see if we can create something that is workable,” said Krauss. “In this case, we were looking for a particular color, a turquoise…and this was our target — this little remnant of a piece of carpet.”

Djuric allowed himself a little hope, which was bolstered as Krauss sent him samples of the dye match.

“Finally, I found a person who not only knows how to dye carpet but has the equipment to dye a small amount,” he said. “Jeff made a small sample and I was ecstatic. Then he made a bigger sample, and my wife was ecstatic.”

Once Krauss and research assistant Alexandra La Pierre (now graduated and working as a testing and standards engineer at Patagonia) found a formula that worked on the woolen carpet, they tested its colorfastness using an Atlas Weather-Ometer to simulate solar exposure. Satisfied with the results, he contacted Djuric, who asked to be present when the full 6-meter roll was dyed.

“I said, ‘By now, I’ve spent five years of my life chasing down this carpet and I would love to see how you do this, if you don’t mind,’” said Djuric. “And he said, ‘Absolutely.’ In January, he let me come down and watch exactly how it was done.”

He flew down from his home in Ohio and was present for the entire dyeing process. Krauss ran the white carpet through the Onomori jig, where it was fed through a series of rollers to wash and scour the material. He dyed the carpet in the same machine, then moved it to the Greenville Machinery padder, where the excess moisture was squeezed out through another set of rollers. The final step was to dry the freshly dyed carpet on the Alea dryer, a machine that dried the material on a long conveyor belt.

Djuric took the carpet home and had it installed in the car, completing the puzzle he had been working for the better part of a decade. The vehicle looked exactly as it had 50 years ago, when his father-in-law purchased it in Europe for $4,375. He has entered the classic car in local and regional car shows, where he has won several awards, and wrote an article about the carpet quest for his car club — which generated interest in ZTE and its capabilities. Since the article, Krauss has twice recreated the dye match for other customers — most recently with the help of research assistant Zoe Millbern.

“People who have these passions for restoring vehicles — and there are many of them — sometimes want products that are no longer available,” said Krauss. “So we get these unique requests. There have been many unique opportunities over the years and that’s what makes the job fascinating — it’s always something different.”

Djuric and his wife plan to pass the restored car on to their children, and could not be happier with the results Krauss was able to achieve with the carpet color match.

“Jeff did a phenomenal job,” he said. “He did what nobody on the planet Earth could do, I’ll tell you that.”

- Categories: