Narrative Thread

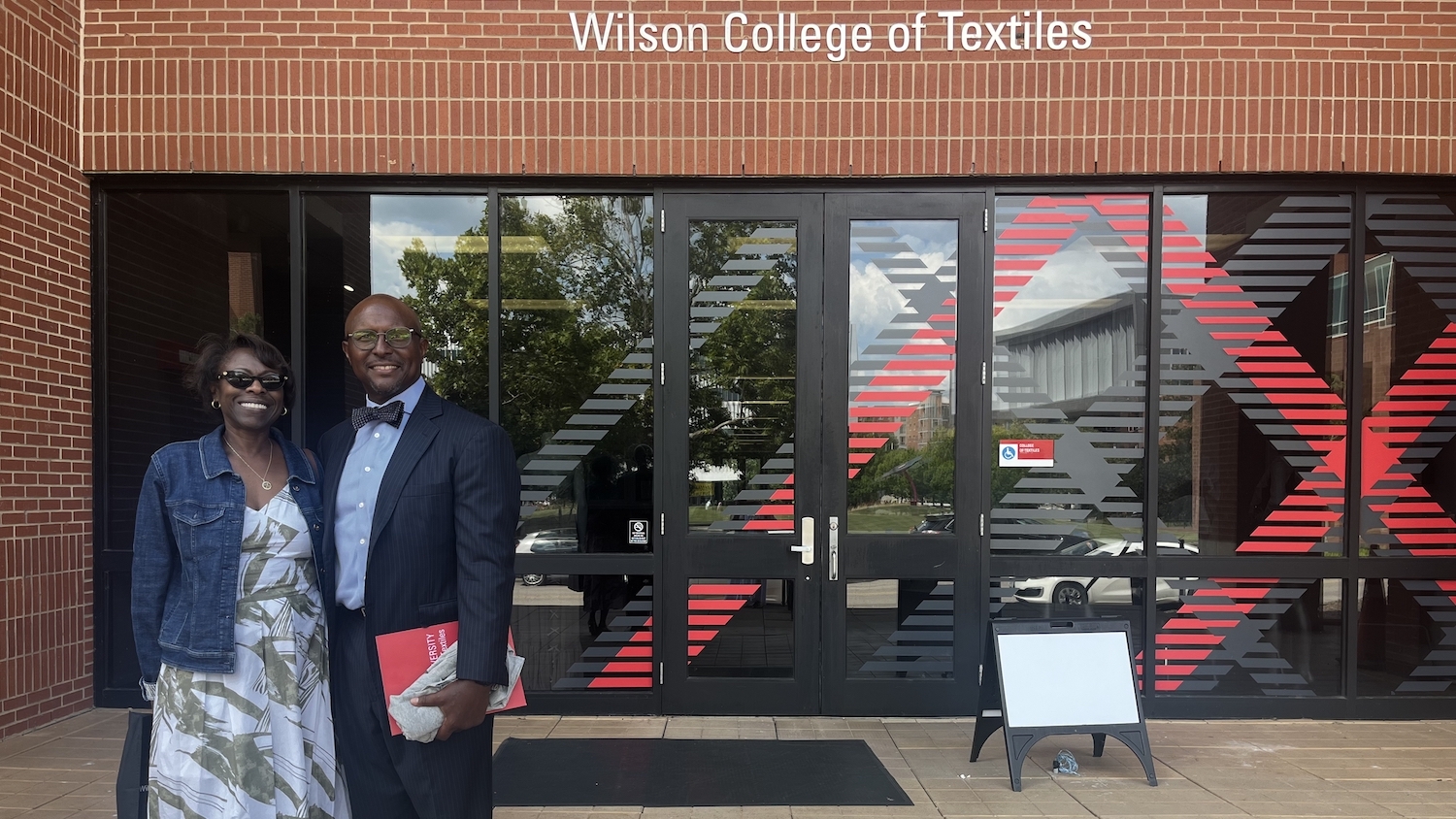

Kate Nartker weaves her magic — then animates it — to show a whole different side to textiles. Photography by Marc Hall ’20, MA.

By Chris Saunders

Weaver Kate Nartker has her latest film project laid out on a couple of tables in a Wilson College of Textiles lab. They’re not VHS tapes or DVDs. They’re not drawings, like ones that might decorate the walls of a Disney studio to show the steps to animation. And they’re not splices of film, which might pile under an editor and director cutting up a movie. No, these are weavings, 5-foot-by-4-foot blankets that each has around 30 frames of action and, as Nartker says, looks like filmstrips. She will animate the panels and weavings to make a movie.

So, yes, Nartker literally weaves stories together.

The weavings depict scenes from her upcoming film about a woman who disappeared in the 1840s, inspired by one of those always-talked-about-but-rarely-followed-up-on family myths. Armed with a self-effacing laugh, Nartker, an assistant professor in the Department of Textile and Apparel, Technology and Management, chuckles at the notion of what she’s planning for a scene — men on horses coming out of the woods as part of a search party.

“It may not work out,” Nartker says. “It may be totally cheesy. I don’t know.”

That not knowing is at the heart of Nartker’s artistry. It’s the freedom of maybe. Maybe what she’s envisioning will work. Maybe not. When Nartker talks about the film, that freedom is there as well as a little fear of the same. But she’s okay with that.

“I wanted to sort of expand the language of textiles. I had this impulse to animate fabric, to see it in a new way. I try to use the loom as a camera.”

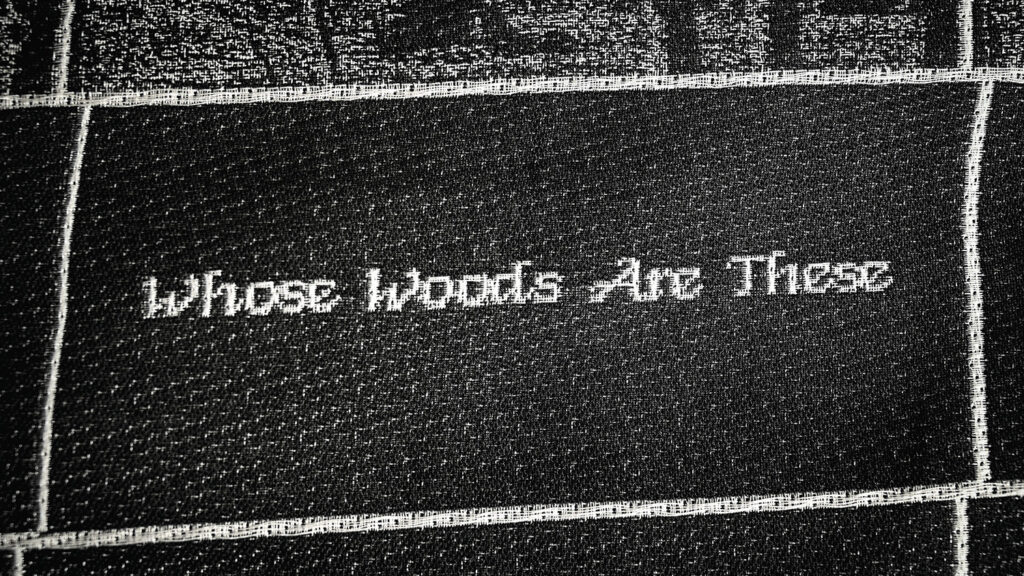

The freedom to explore is what first drew Nartker to animating weavings more than a decade ago. Her work has been featured in international galleries as well as The Museum of Craft and Design in San Francisco, the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art and The Contemporary Austin. Her latest project, “Whose Woods Are These,” will be her longest work and her first foray into a fully imagined narrative film. The seven-minute short is Nartker’s re-imagining of the unsolved 1841 disappearance of her great-great-great-great grandmother in Ohio. The project is one part tapestry, one part Pixar, with dashes of mystery and 19th century romanticism on top.

It features themes — such as memory, fragmentation and emancipation — present in all of Nartker’s work as she’s married fabric and film for the last decade.

“I wanted to sort of expand the language of textiles,” says Nartker. “I had this impulse to animate fabric, to see it in a new way.

“I try to use the loom as a camera.”

First Films

The idea of telling a story captured on cloth is nothing new. Nartker points to the medieval Apocalypse Tapestry, a 14th century woven tale of the Book of Revelation measuring some 450 feet and spanning 90 scenes. Then there’s the Bayeux Tapestry, 230 feet of embroidery from the 11th century that tells the story of the Norman Conquest and is stretched out on display in a museum in Normandy, France. “These are heralded by film critics as being one of the first records of cinema,” Nartker says. The Bayeux Tapestry, she says, has evidence of flashbacks, foreshadowing and other cinematic techniques. “Those were first found in these narrative textiles.”

It’s hard not to think about those tapestries when looking at Nartker’s blankets laid out in the Wilson College of Textiles lab. Each weaving depicts a scene from “Whose Woods Are These” and contains many frames, each with the slightest variance to show movement and the progression of the scene. It’s the same concept as the rudimentary stick figure drawn in the corner of grade-school notebook paper that appears to run when the pages are flipped. And that’s where Nartker’s art builds on the 11th- and 14th-century weaving masters. Those guys never saw Toy Story.

Spinning a Yarn

Kate Nartker relies on black and white yarn, computers, and a big, green monster to weave together her stories and bring them to life.

The process Kate Nartker uses to animate her weavings is more than a decade old, and she has it down to a science.

She scans in the frames from the footage she’s using into Photoshop. She then sends the files of all the frames for a scene to one of two looms in the Wilson College of Textiles. This is the most labor-intensive part of the process.

One of the destinations is a Jacquard loom, traditionally used to produce home interior and upholstery fabric. It’s a green behemoth industrial machine with two levels, and it looks to swallow up Nartker’s small frame while she waits for the automated loom to send the cloth off the roller. Unlike traditional weaving, she says, “Jacquard weaving is different because each thread on the loom can be lifted individually, which enables you to weave photo-realistic imagery.”

The second loom she uses to manually weave what she wants is the TC2, another digital Jacquard loom. There are only about 50 of these in the United States. It’s smaller than the other and can frustrate its user. “Yarns break all the time, so you’re always kind of wrestling material and your digital file simultaneously,” she says. “But it’s super fun textural stuff.”

Once the weavings are off the loom, Nartker paints color on to the black and white yarn. In “Whose Woods Are These,” she includes vibrant yellows and greens, belonging to grass and an inchworm inching along, signaling her protagonist’s walk into a new world, much like we see color bringing to life Dorothy’s Oz.

After painting on color, Nartker scans the fabric into the computer as a digital file and animates them at six frames per second. (The animation of a PIXAR movie is set at 24 frames per second.) Producing one animated scene may take a week. Then the sound is added, as well as the musical score, which Nartker’s husband composes.

Color and Structure Tell a Narrative

Nartker’s dalliance with animating her weaving and bringing them to life began in 2010, when she was pursuing an MFA at the California College of the Arts. Her videos, each between 30 seconds to a couple of minutes in length (she says that equals about eight feet of woven cloth) and on display on her website, simply depict pattern changes on a particular weaving. Threads of orange and white turn to blue and yellow. Patterns of rectangles running linearly across the screen change form to vertical blue-and-white patterns framing an orange checkerboard pattern running horizontally. Nartker believes an animation can tell a story without having to rely solely on a narrative. “There’s other ways to glean meaning,” she says, “from the color interactions and the structural connections.”

Other animated weavings in her collection show lovely fleeting moments, like her sister riding a 10-speed bike or kids gleefully see-sawing, found on her father’s old VHS tapes of home movies. There’s one where a TV is playing an old VHS tape, and Nartker accounted for bad tracking with woven distortions rolling up the screen. She says that represents a theme of her early work. “It was really about this connection between the way materials degrade, like a VHS tape, or thread on a dress, and how that parallels the way we think about memory and the way we think about things,” she says.

“It’s sort of like a visual material representation of what happens to us.”

A Little Nugget

One of Nartker’s weavings on display in the lab stands out. The initial panels at the top show a black and white forest of trees blocked off by heavy black frames on the right and left. A couple of rows down, a silhouetted body peeks out from the right and enters the scene as the frames progress. The figure stands sturdy in what is a doorway. By the last panel, the figure disappears from the frame and the woods come alive. When animated, it will take the viewer into the scene. The technique illustrates what Nartker believes film can accomplish that textiles, unanimated, can’t. “[Textiles] don’t invite the viewer to look in at a specific focal point,” she says. “It leaves you at the surface.”

That figure there is Nartker’s protagonist in “Whose Woods Are These,” an imagined 19th century American woman who escapes her domestication to explore the romance of the natural world outside her door. Nartker says when she first conceived of making this movie in 2012, she didn’t know where her protagonist may end up. “I just started by having her walk. Walk toward the woods,” she says. “And then I, at some point, decided I wanted her running away. This was a decision she made, to leave.”

Nartker doesn’t know what Julianna Hofrichter, her great-great-great-great grandmother, decided or where she ended up. Nartker says she first heard of this family legend when she was in graduate school animating weavings. “There’s just this little nugget,” she says. “I was working with my dad’s footage and kind of digging into my family’s history, and this was mentioned.”

Nartker didn’t find much to help fill in the family myth. She has a couple of maps from the era depicting what Henry County, Ohio — Nartker grew up there in the city of Napoleon — looked like in the 1840s and some genealogical lists. She has some writings from the county’s historical society describing the wild, dense forests of northern Ohio. And she has a 1930 interview the Napoleon (Ohio) Northwest News conducted with her grandfather, who had gone to gather hickory nuts with Hofrichter, his grandmother, on the day she disappeared. It’s the only record providing any details of Hofrichter’s disappearance. “I got tired and she helped me home and went on to pick more nuts,” he said. “Grandfather came home in about an hour and on learning where she was, set out immediately to meet her, saying we should not have left her thus alone.” The family and neighbors searched, but never found her.

Nartker’s fine with not knowing Hofrichter’s fate. It allows her to explore. It permits the maybe. “I prefer . . . imagining this story of her just wanting to live this wild life,” she says. “It’s kind of exciting to imagine some woman in the 1840s running away from all her responsibilities.”

A Material Girl

Nartker plans to finish “Whose Woods Are These” by the end of this year. (She’s a little sidetracked now, lecturing in Sweden as one of four of NC State’s 2022–23 Fulbright Scholars.) When the film is done, she plans to submit it to the Sundance Film Festival. And she’ll have an exhibit featuring the weavings that tell the story. By the time she’s finished, she’ll probably have woven at least 200 feet of cloth for her seven-minute short.

Though the short is longer than anything she’s done, her themes are still there. The movie contains a close-up of an owl’s head that flickers between clarity and distortion. “There’s a lot of inquiries into abstraction. I think I have a lot of examples of this where the image comes in and out of focus,” she says. “It’s this new way of abstracting an image by its own physical makeup.” And the film even includes some Easter eggs. There’s a scene of the protagonist walking in the woods. The imagery soon turns into a scene of a fabric waving in the wind. The weaving on that fabric is a nod to a historic pattern from Anna Maria Garthwaite, one of only a handful of prominent female textile designers in the 18th century.

When asked about her process, Nartker admits it’s been piecemeal, calling on a textiles analogy to explain. “It’s not at all been a linear thing,” she says. “It’s almost like making a quilt, taking pieces of this and pieces of that.”

Nartker again depends on that same image of a quilt to capture the main reason the film holds a logical spot in her progression as an artist — it’s that she has an essential belief in the material.

“Textiles tell a story on their own,” she says. “If you save a quilt and it passes down from one generation to the other, it’s threadbare and it’s been mended.

“Those are stories.”

See Kate Nartker’s animated weavings as well as a preview for ”Whose Woods Are These.” https://www.katenartker.com/

This story originally appeared in NC State Magazine.

- Categories: