By Sarah Stone

Fallen leaves crunching under their feet, 8-year-old William Sauer walks into the dense woods of Henry County, Ohio, with his grandmother to collect hickory nuts.

When the family adventure begins to feel like a chore, William asks his grandmother, Juliana Magdalena Hofrichter, to take him home. After walking him back to their house, she returns to the forest to finish up.

This is the last time anyone will report seeing Hofrichter.

“They searched [for her] for hours, for days and weeks, with all the neighbors helping,” Sauer says in a 1930 interview with a reporter from the Napoleon Northwest News. “And though that was nearly ninety years ago, we never found a trace of her.”

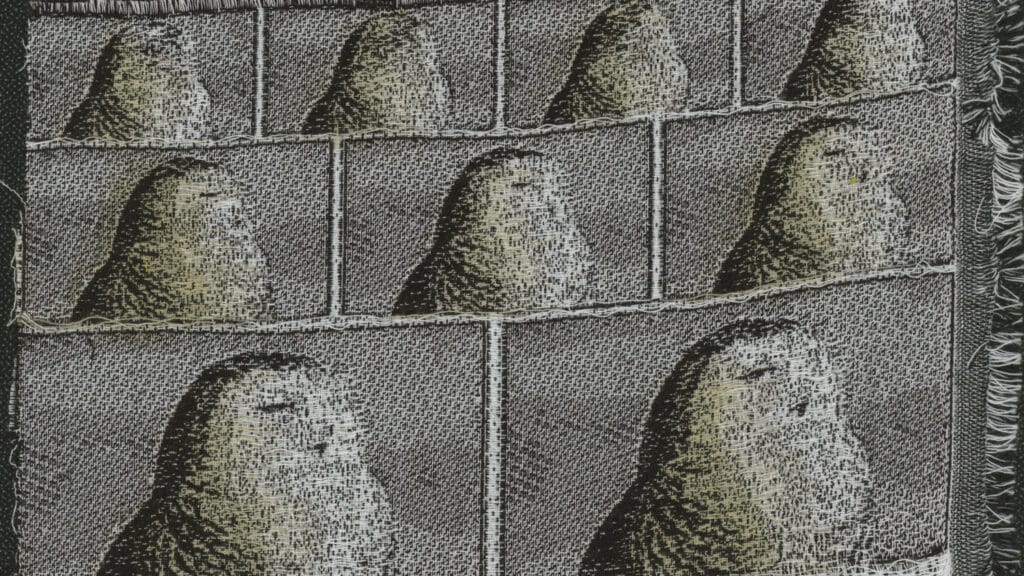

This 1841 cold case is the inspiration for Kate Nartker’s debut film, “Whose Woods Are These?” Nartker, an assistant professor at the Wilson College of Textiles, develops her weavings into film through frame-by-frame animation (read how). The trailer for the upcoming short film debuted in October.

“What really intrigued me was the mystery of nobody knowing, as well as the centuries-old tradition of using textiles to tell stories,” she says.

The “mystery” is also a piece of family history; Hofrichter was Nartker’s great-great-great-great grandmother.

Not in the “true crime” genre

Nartker says her ancestor’s disappearance serves not as the plot but instead as a point of departure. In Nartker’s fictional spinoff, a Midwestern woman leaves her life behind. Enchanted by nature and enveloped by the forest, she finds renewal in the wilderness.

“Whose Woods Are These?” derives meaning from Robert Frost’s poem “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening,” a man’s love letter to the great outdoors. The goal, she says, is to call attention to a lack of representation of women in these fictional spaces.

“There are literary examples of a man wanting to leave and live isolated in nature, from ‘Walden’ to ‘Robinson Crusoe,’” Nartker says. “But there aren’t that many stories of women who want to go live in the wild.”

Initial reactions to her work have only amplified her point of view.

“As I work on the project, people ask what her responsibilities were. ‘Did she have kids?’” Nartker says. “These are questions that never are asked of men in other stories.”

History, heritage and family

Nature itself quickly emerges as a secondary character of the film. Landscapes are shown in colorful contrast to the mostly black and white depictions of Hofrichter and domestic scenes.

“It’s this story of someone being swallowed by or disappearing into the land,” she says. “Yes, it’s about disappearance, but it’s also just about this region, this history, which is fascinating, too.”

This region in Northwest Ohio was once called the “Black Swamp” because of its marshes and dense forests. Nartker has used historic maps of the area where Hofrichter disappeared, Google Satellite images and other resources to study the landscape.

She says when Juliana Magdalena Hofrichter disappeared in the 19th century, the Black Swamp would have been filled with creeks, black bears and wolves. Since then, commercial agriculture has rendered the land flat and bare.

“You can see forever. Most of the trees have been cut down, and it’s completely flat now,” she says. “It’s impossible to imagine anybody vanishing.”

Although the landscape changed, Nartker’s family remained.

“My grandfather was the mayor of the small town where my ancestor disappeared,” she says. “My family on my mom’s and dad’s sides have settled there and lived there for many, many generations.”

History, family and heritage are intrinsic to Nartker’s artistic identity. Her father, a photojournalist, inspired her first artistic interest: photography.

Nartker returned to her father’s work as a source of inspiration when studying for her Master of Fine Arts at California College of the Arts. She says his old film reels were some of the first scenes she wove and animated.

The loom as a camera

This intersection between textiles and film is the foundation of Nartker’s research and a central theme in her body of work.

“There is an understudied history on how textiles and cinema have informed one another, and this drives much of my work,” Nartker says.

While Nartker’s research is now rooted in this historical and theoretical intersection, it grew out of simple curiosity.

“I wanted to see fabric move, or the illusion of fabric moving in a 2D space,” she says. “It really comes down to expanding the language of textiles.”

That means using the loom as both a camera and a video editor. She uses thread and weaving techniques to zoom in on a subject or change scenes.

“In my trailer, there are certain scenes that fade to black, and it’s because of the warp and the weft – black threads coming to the surface,” she explains. “A structural inquiry that drives a lot of my work is, ‘How can I materialize these cinematic techniques?’”

Weaving has a reputation as a traditional art form, but Nartker’s work is nothing short of innovative. Simply put, she has pioneered the technique of woven animation.

“It’s visionary to pinpoint textile crafts and traditions as material for digital expression and reexamination,” Victor De La Rosa, Director of San Francisco State University’s School of Art, says of Nartker’s work.

Loop videos of Nartker’s animated weaving scenes have appeared in galleries from South Korea to Norway. “Whose Woods Are These?” marks a move away from individual, abstract scenes to a longer, cohesive film.

“The context in which something is viewed changes everything, and I want the experience of showing a narrative film in a theater setting,” she says.

How does she do it?

“Someone once asked me, ‘Aren’t you scared someone’s going to steal this idea?’” Nartker says jokingly when asked about her technique. “And I told them, ‘No one in their right mind would want to do this.’”

That’s because going from inspiration to woven film is an arduous, convoluted process.

First, Nartker records a video of the scene she wants to weave and uploads it to a software that splits the video into individual still frames.

Next, she develops design files for each still frame using Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software that she then weaves by hand or sends to an industrial loom. After hand-painting over some of the weavings, Nartker scans each woven “still” and edits them back into a video, resulting in the frame-by-frame animation.

From art to academia

“Whose Woods Are These?” originates from Northwest Ohio history and heritage, but Nartker believes this project would not be possible without support from the Wilson College.

“I could not do this anywhere else, hands down,” she says. “I think NC State is unmatched in that we have so many incredible tools and applications.”

Senior textile design student Anna Stuffelbeam enrolled in an advanced weaving course with Nartker last year. She says Nartker’s unique work sparked inspiration for her own award-winning photorealistic weavings. Judges from the Surface Design Association (SDA) selected art woven by Stuffelbeam to be showcased in a virtual exhibition last year.

“She was really helpful in how to put together the application, how to write the artist statement, how to present your work,” Stuffelbeam says.

Nartker’s advancements in the weaving world are also gaining attention from internationally-renowned research organizations.

In June, she was named one of three Fulbright Scholars chosen from NC State. She’ll head to Sweden in the spring of 2023 to teach weaving at HDK-Valand at the University of Gothenburg while learning from the region’s world-renowned weaving artisans.

“My focus there will be on complex traditional weave structures. My goal is to apply them to the project: to work with transitions between scenes and execute cinematic effects, but through structure,” she says.

Nartker plans to enter “Whose Woods Are These?” into juried film festivals by the end of 2023. She freely admits that the plot of the film remains somewhat of a mystery even to herself. In the meantime, she’ll continue to research the narrative potential of textiles, allowing the magic of nature and escapism to inspire her.

“She’s going to reach the woods and find enchantment and wonder,” Nartker says. “It’s going to be a lot of experimentation.”

- Categories: